Tattoos and piercings are an expression of my interests and a permanent record of my life

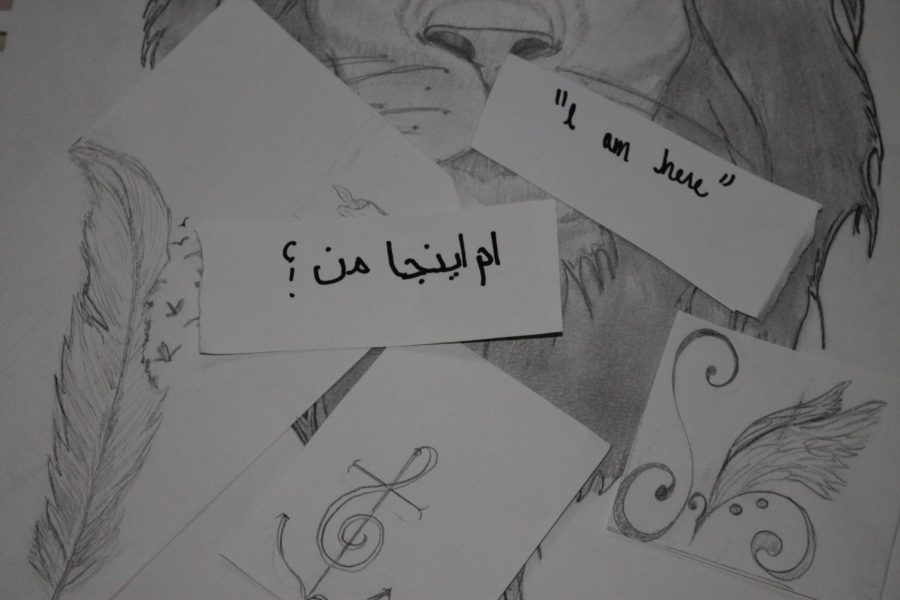

A collection of tattoo sketches from the author’s adolescence.

April 30, 2018

My fascination with tattoos and body modification began when I was in elementary school. I have always loved elaborate piercings and artwork that incorporates the body. Tattoos and piercings not only allow people to admire artwork but to become art themselves. My tattoos function as both an expression of my interests and a permanent record of my life.

My late grandfather had an assortment of tattoos, from the skunk tattoo across his chest to the pin-up girl that leaned against a palm tree on his calf. When I was a little girl I would sit beside him on his yellowed couch and count the tattoos on his forearms while he watched television.

Growing up, I had only seen men with visible tattoos; the first time I saw a woman with visible tattoos I was mesmerized. I began sketching designs that I hoped to get tattooed one day- much to the frustration of my mother. I drew dozens of tattoos: a lion to symbolize courage, pine trees to symbolize my love of nature, verses of scripture in a myriad of fonts. After completing each drawing I would march them up to my mother.

“This is what I’ll look like as an adult!” I’d say. My mom clicked her tongue in disbelief.

By the time I was 17 I had tattooed myself twice. My first tattoo, which I refer to as a “trial tattoo,” was an homage to my love for J.R.R. Tolkien. Using a needle and calligraphy ink, I tattooed the word “love” in Tolkien Elvish on my upper thigh. While I had not expected this tattoo method to be truly permanent- it was. Nearly a year later, I gave myself a parallel tattoo of a “nazar,” a Middle Eastern symbol of protection from evil. This design was the first piece that incorporated my Islamic faith.

After my first “trial” pieces, I acquired two large tattoos that had great personal meaning to me. The first is a large black-and-white tattoo of a lotus flower with the eating disorder recovery symbol in place of the flower’s stem. The second piece is a replication of Bilbo Baggins’ home in Lord of the Rings that spans the majority of my left thigh. Both pieces of artwork were designed and tattooed by a family friend during her apprenticeship with a professional artist.

Though I had planned to receive professional tattoos shortly after turning 18, it wasn’t until recently that I was tattooed by a career artist in a tattoo shop. For my first professional tattoo, I chose a design that celebrates my faith as a Sufi Muslim.

The front of Mad Dog Tattoo, where the author was tattooed.

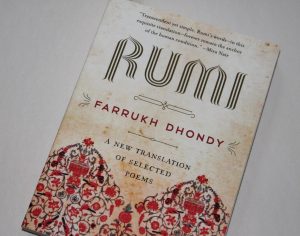

Sufism is a form of Islamic mysticism, similar to Kabbalah in Judaism or Catholic mysticism in Christianity. While most Americans have been exposed to the writings of popular Sufi figures such as Rumi or Hafez, they rarely recognize that the literature is rooted in Islamic theology. In fact, most English translations of Rumi’s literature remove most of the cultural and religious references entirely. Because of the lack of understanding about Sufism, Sufi Muslims are often misidentified as a separate sect of Islam and therefore subjected to religious violence.

The idea for my religious tattoo started with the last phrase of a Rumi poem: “To every call of ‘Oh Allah,’ He answers a hundred times ‘I am here.’” I stumbled upon the poem while I was hospitalized for my eating disorder. Because the poem brought me great personal comfort, I decided I would someday have the phrase tattooed on my chest. I wrote it down in a notebook for safekeeping and the thought fled my mind soon after.

Years later, I came across the poem in a newly purchased collection of Rumi poetry. It felt like an omen. The final line of the poem still filled me with confidence and warmth- and I was just itching for a new tattoo.

I had planned to tattoo the phrase on my chest, but I hadn’t arranged how I would fit such a lengthy phrase under my collarbone. After some deliberation, I reduced the phrase to “I am here.” The shortened version of the sentence left more room to interpretation. “I am here” refers to both the Sufi poem and my presence as a corporeal form. Since the shortened line did not require careful arrangement on the chest, I placed the design just above my heart.

I printed out the design, folded the paper in half, and drove to the nearest reputable tattoo parlor. Luckily, an artist who specialized in foreign language tattoos was there. We made an appointment for the next day.

I arrived at the tattoo parlor 15 minutes early, hands shaking with excitement. I sipped my cranberry Red Bull and waited for the artist. After nearly 40 minutes had passed, the artist pulled into the parking spot beside my car, swearing and apologizing profusely. We began setting up for the tattoo process.

He placed the stencil on my chest, stood back, and frowned.

“It’s not right,” he mumbled to himself.

The edition of Rumi poetry that inspired the author’s tattoo.

He wiped off the stencil, placed it on my skin once more, and frowned again. He repeated this process three or four times until he was pleased with the placement. He gestured for me to check the placement for myself in the mirror. I nodded, and the tattooing began.

I laid on my back and folded my hands on my stomach. Once I heard the familiar buzz of the tattoo machine, I exhaled deeply. The last piece I had tattooed was incredibly painful and took a total of five hours to complete due to its size. This tattoo was small by comparison and would only take 20 minutes to complete.

Much to my surprise, the tattoo was painless. The artist was attentive and kind, frequently asking if I was in pain. We chatted while he worked, discussing politics and Islam. He asked me about my faith and the translation of the tattoo, which is in Rumi’s native Farsi. Once the tattooing was completed, I walked to the mirror to examine my new artwork. Pleased, I turned to the artist and smiled.

I spent the next week stopping to admire my tattoo in every reflective surface I could find.